Rev. Jared Buss

Pittsburgh New Church; July 6, 2025

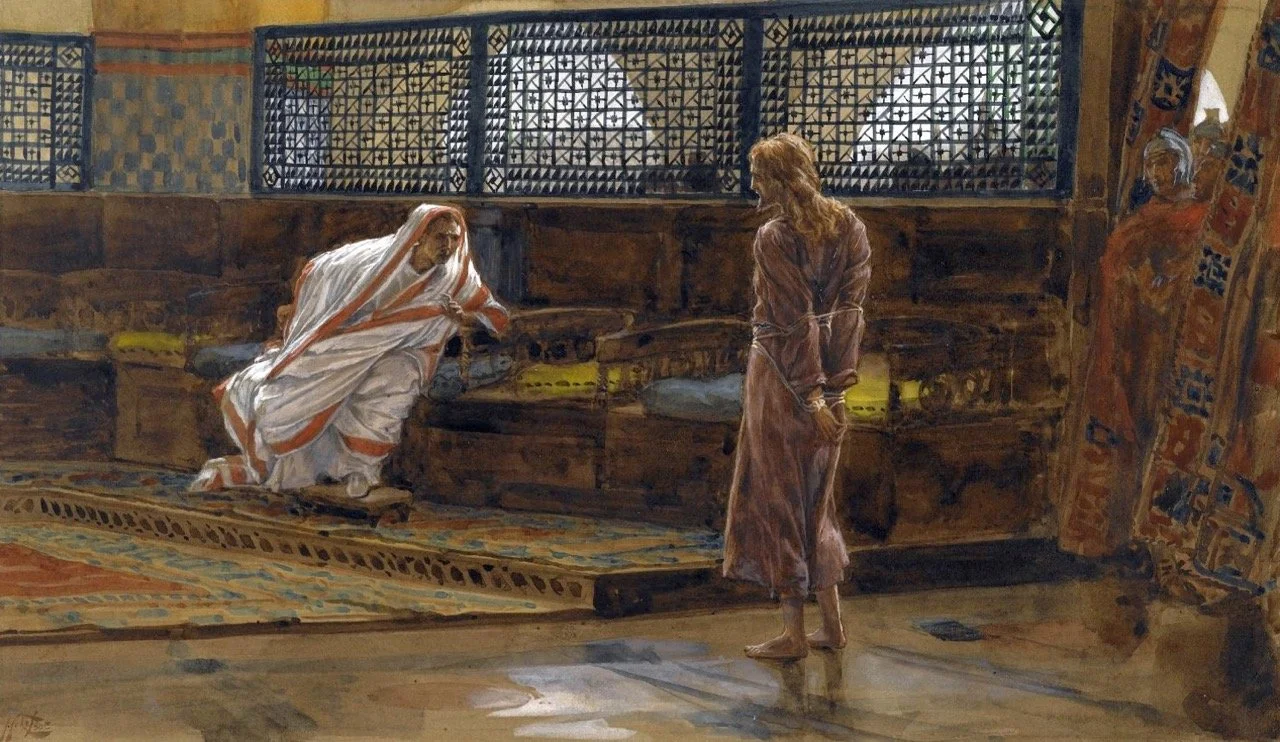

Readings: John 18:33-37; True Christian Religion §414 (children’s talk); True Christian Religion §305

Video:

Text:

The sermon today is about love of country. The teachings of the New Church make it pretty clear that we’re supposed to love our country—but what do they mean by that? What is it about our country that we’re supposed to love?

We’ll begin by looking at what the Word says. In the book of Exodus we’re given the Ten Commandments, and the fourth commandment says: “Honor your father and your mother, that your days may be long upon the land which the Lord your God is giving you” (20:12). In the book True Christian Religion there’s a chapter on the layers of meaning within the Ten Commandments, and the section on the fourth commandment reads as follows (you can find this reading on the back of the worship handout): [read §305].

That statement that one’s country is called one’s “fatherland” makes more sense in the original Latin of True Christian Religion than it does in English. This country is almost never called “a fatherland.” But in Latin, the word for country—patria—is closely related to the word for father, pater. So if you’re reading in Latin, the word “country” is going to make you think of the word “father.” And the teachings invite us to think along similar lines, even though we speak English and not Latin. Our country is like a parent to us.

The fact that love of country is covered by the fourth commandment makes it pretty important. The Ten Commandments are kind of a big deal. The teachings of the New Church consistently say that the things we need to do in order to get to heaven are 1) acknowledge God and 2) keep the Ten Commandments. And that does mean all of the commandments. It’s obvious that murder and adultery and stealing are bad. But commandments like, “You shall have no other gods before My face; “remember the Sabbath;” and “honor your father and mother” are given the same weight as the commandments against murder and adultery and stealing (Ex. 20:1-17). If keeping the Ten Commandments is essential to the life of religion, and loving our country falls under the umbrella of the fourth commandment, then it sounds like we need to figure out how to love our country.

This makes it important that we understand what it means to love our country. Because let’s be realistic: there’s probably nobody alive who loves everything about their country. It’s pretty obvious that the country we’re in—the United States of America—is imperfect; and some of the country’s imperfections are troubling. Different people are bothered by different aspects of the country’s imperfection, but surely all of us see something we would change. And we get our backs up if we feel like we’re asked to love things that bother us, things that we think are wrong. “Love of country” sometimes smacks of blind patriotism and jingoism, and those things are not good. That kind of love of country can’t be what the Lord wants. We don’t have to love things that we think are wrong. But the Word says that we should love our country. So how should we love it? Or what should we love about it?

It seems likely that when we talk about “our country,” our minds are drawn towards thoughts of the government, or of national politics, or foreign policy—thoughts of America’s role on the world stage, or the impressions that she leaves with people from other countries. These things are part of the country: they contribute to the country’s identity. But they’re not what it is. A country is not a government—it’s a group of people. In America’s case, we’re talking about roughly 340 million people who share some sort of common identity. By the way, we’re talking specifically about America today, since that’s the country that we’re in right now, and since we just celebrated America’s Independence Day; but the teachings that we’re considering apply to every resident of every country in the world.

The teachings of the New Church do talk about love of country in context of honoring father and mother; but most of the time when the teachings talk about love of country, the context is love for the neighbor. And that’s illuminating. Love of country is an extension of love for the neighbor, and love of the neighbor is about loving people—or the good in people. The general teaching is that there are degrees of the neighbor, and a large body of people is the neighbor in a higher degree than a small body of people. So a community is a higher degree of neighbor than an individual; a country is a still higher degree of neighbor; above our country is the church; and above the church is the Lord’s kingdom (SH §§6818-6824; NJHD §§91-96; TCR §§412-416; Charity §§72-89). To put it simply, loving a more people is more loving than loving less people. In True Christian Religion we read: “Love towards the neighbor can rise to ever more interior levels in a person; and as it rises it is directed towards the community rather than an individual, and towards the country rather than the community” (§413). As our love rises higher it looks further and encompasses more. It extends beyond our personal spheres to the bigger bodies that we’re part of. There are 340 million people who make up this nation, and there are a lot of things that we share with them; what do we share that’s worth loving? Those people, and the good things that we hold in common with them, are the country that we’re meant to love.

But then, the planet holds about eight billion people, and that’s more than 340 million. Why don’t the teachings simply say that we should love everybody? Why don’t they say that we should love our fellow human beings regardless of their birthplace and their citizenship and so on? Well the Word does say this in lots of places. It says that love for the Lord is the highest love, because when we love Him we love all of His people (TCR §416; SH §2023). In The Doctrine of Charity we’re told that the human race is the neighbor in the widest sense (§87). We are supposed to love everybody—or, more accurately, we’re supposed to love the good in everybody. We mustn’t set our own country too high. The church is meant to be above our country, and the Lord’s kingdom above that, and the Lord above all (cf. SH §6819; NJHD §91). But love of country still gets its own moment. It falls under the umbrella of the fourth commandment, and we need to keep that commandment. There’s a particular space that we should hold in our hearts for the country that we happen to live in.

And why is that? One reason we should love our particular country is that our country has served us in a particular way. As the reading from True Christian Religion says, our country is like a parent to us: it has fed us and protected us (§305; cf. §414; SH §6821; NJHD §93). That’s true in a very literal way. If everyone in this country besides yourself were to disappear tomorrow, along with everything that those people have made or built, what would you have left? How would you feed yourself? Our country gives a lot to us, and it should be honored for what it gives. The same is true of our actual parents—our mom and our dad. They’re not the only people in our lives, and they’re certainly not the only people that we should love. But they play a special role, so they should be honored in a special way.

A slightly bigger principle that’s at play here is that it’s useful for us to work with what’s in front of us. Another way to put it is that you have to be God to hold the world in your hands. The Doctrine of Charity points out that the nations of this world don’t always want what’s best for each other (§85). We wish that it weren’t so, but it is so. In practice, doing things that appear to be in the best interests of other countries may well mean that we’re working against our own country. Because of this, we’re told that we have a duty or an obligation to do good to our own country, and that we don’t have the same duty to serve countries other than our own (ibid.) This is easiest to understand if we imagine being attacked by another country. In that situation America’s people would have an obligation to defend her; we wouldn’t say that they had an obligation to fight for the other side. It’s easy to say that we should just love everybody, but in practice, loving people means trying to do what’s good for them—and it’s hard to figure out how to do good to everybody all at once, especially when people are fighting with one another. Again, the principle here is that you really have to be God to hold all people in your hands. We’re limited; and if we want to actually be useful, we need to center ourselves on the things that are within our reach. This doesn’t’ mean that people from other countries don’t count—they’re still the Lord’s people. It’s just a general principle that the closer we are to home, the more power we have to do something that will actually be useful.

Here we are, for better or for worse, in this bucket, this category called “America.” At the end of the day, our options are to love what’s around us or to not love it. We don’t have to love everything about it—this is something that the Word makes very clear. The neighbor isn’t really other people so much as it is the good within other people (SH §§6706-6709; NJHD §§86-88; TCR §410; Charity §§46-54). The America that we’re supposed to serve is whatever it is that’s good that we share with other Americans. This means that we’re allowed to distance ourselves from the characteristics of this country that we don’t like (cf. Charity §86). We’re allowed to object to laws that we think are unjust—as long as we do so lawfully. But what good things bind together the people in this bucket? What do we share that’s worth loving?

A useful thought exercise is to picture this country as a single person. If America, with all of her different values and ideals and flaws, were to take physical form as an ordinary human being, what would that person be like? We’re actually told that this is something that happens in the spiritual world: whole countries or communities are seen as individual human beings (TCR §412; Charity §84). The characteristics and affections of those countries are represented in the face and in the behavior of the human form that they take. If America were to take human form, how would she behave? What would she value? She wouldn’t be flawless. But something that comes to light if we picture the country as an individual is that it’s both useless and unkind to look at any individual and note only what’s wrong with them. We shouldn’t love our country blindly or excuse her flaws, but sometimes it seems that it’s fashionable to look at the nation and observe only what’s wrong with it. We know that it would be unkind to treat an individual that way. Why treat a country that way?

What would this personification of America actually be like? The Word doesn’t say anything about this country, and we can’t see her the way that the Lord and the angels do. All we have is our own impressions. There are some national characteristics that are widely acknowledged and have contributed to a shared sense of the country’s identity: Americans value the individual’s right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Americans value freedom of thought; so this country has passed laws protecting freedom of speech and of religion. Paradoxically, America is a country in which slavery was once institutionalized. She’s also a country that has passed laws forbidding slavery

Heaven knows that this country isn’t perfect. But heaven also knows that it’s useless to look only for what’s wrong with something. For better or worse, here we are amidst millions of Americans—and those people are building on the work of millions more who have already come and gone. None of those people were (or are) perfect. But what good things do we share with them? What do we have to be grateful for? What potential do we share? That common good is bigger than any of us—and that’s why the Word says that we should honor it as we honor our father and our mother.

Amen.